Overview

In my previous post, I wrote that distributed processing probably wouldn’t be necessary for a few thousand connections. However, I reconsidered and decided that we should still design it to handle the load properly. If we implement distributed processing well, I think we could use cloud services to conduct some interesting experiments. So, I’ve come to see this as an area where we should put in the effort (I’ll explore this further in a future post). I also felt it was a bit presumptuous to use a grand title like “Implementation Methods” without actually explaining anything. So, this time, let’s consider how to distribute processing for a multi-table tournament.

Distributed Processing System

Distributed processing systems are often employed for computations with heavy loads or systems involving a very large number of network accesses. When implementing distributed processing, roles are typically divided between servers (child machines) that execute the target processing—such as computational tasks or handling requests and returning responses—and servers (parent machines) that manage the overall progress of the processing and distribute tasks. This system configuration was historically referred to as a Master/Slave architecture. Nowadays, the term “Slave” is considered discriminatory, so the architecture is often referred to as Master(Controller)/Worker, Leader/Follower, or Parent/Sub system.

When implementing a multi-table tournament using a distributed processing system, the standard configuration typically involves preparing servers to fulfill the roles of parent and child units. The child units handle socket connections with clients, while the parent unit manages overall game progression instructions and aggregates various statistical data. Since poker involves minimal CPU- or memory-intensive processing like calculations, it seems feasible to have child machines handle only communication while concentrating game processing on the parent machine. However, when playing games that include NPCs (AI), executing AI decision algorithms (like Monte Carlo simulations) may incur significant computational costs. Therefore, we will examine the distributed processing mechanism assuming that the child machine manages game progression for each individual table, while the parent machine handles only the overall progress management of the MTT.

Since a multi-table tournament can be divided into the following phases, we will consider the processing of the parent and child machines for each phase.

- Participant Recruitment Period (Before Game Start)

- Participant Recruitment Period (After Game Start)

- After Recruitment Deadline

- Game End

Participant Recruitment Period (Before Game Start)

Before the game starts, the system only accepts participant registrations, requiring minimal processing. However, since it needs to communicate initial messages and information to participants, it must maintain socket connections. Even though no communication occurs, the need to maintain connections means distributing connection targets should be planned from this stage. Two approaches for distributing socket connections to client machines can be considered. Since they seem to offer little difference, the easier-to-implement method should suffice.

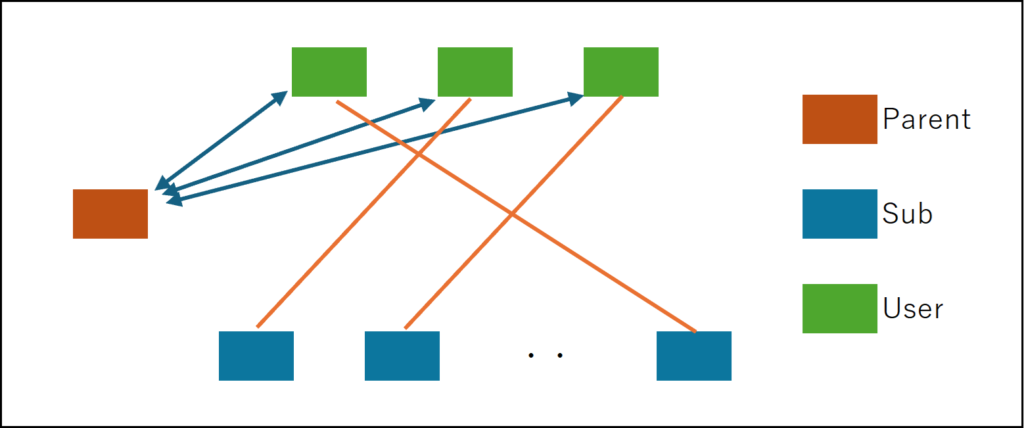

The first method involves clients notifying the parent server of their participation via a REST API or similar. In response, they receive the IP address of the target server and establish a socket connection to that child server. For example, the parent server could control the connection destination using a table balancing algorithm, ensuring players assigned to the same table connect to the same server.

The other approach involves clients randomly establishing socket connections to child machines based on User IDs or IP addresses, then sending participation notifications (a load balancer could be used for assigning child machines). Child machines receiving these notifications aggregate participant information by transferring it to the parent machine via server-to-server communication (backplane).

In either approach, the parent ultimately holds aggregated participant information, while clients are distributed across sockets connected to various child units. The former method, requiring the parent to pre-possess child unit information, may be effective when building services using a fixed number of rented servers. Note that if you want to automatically scale child nodes using cloud services, the child nodes must be designed stateless (meaning they cannot hold user-specific information or data, as users cannot control which child node they connect to). This leaves only the latter approach as an option. While the latter seems like the more sophisticated method, it appears neither approach should cause issues.

Incidentally, when I asked Google Gemini, it labeled the former as the stateful set strategy and the latter as the routing header strategy. It recommended the latter strategy when using Google’s cloud service (Google Kubernetes Engine). Conversely, ChatGPT tends to recommend the former approach, suggesting that the latter method might cause the backplane (like Redis) to become heavily loaded and create a bottleneck. If you want a feature like auto-scaling based on processing load, the latter approach is preferable. However, if you can estimate the processing load to some extent, the former method (where child nodes manage state) might be better to minimize communication volume.

Participant Recruitment Period (After Game Start)

Multi-table tournaments typically accept additional participants for a set period after the game starts, or allow re-entry for players who were eliminated quickly. During this period, participant acceptance processing and game progression processing must run concurrently. Participant acceptance can be handled the same way as described in the previous section, but initially, participants should be placed in a waiting list without assigned tables. Table allocation should occur during the Table Rebalancing process.

Game progression processing is fundamentally as described in the previous post. However, since the client machines hold the game progress and results for each individual table, information sharing between the parent machine and client machines is necessary. The timing for this information sharing is at the end of each game. The client machines notify the parent machine of each player’s stack change amount, eliminations (players whose stack reached zero), and the number of players at each table.

There are two approaches here: if messaging middleware between servers can be used as a backplane, client machines can send end-of-game data for each table to the parent machine. In return, the parent machine would provide overall MTT statistics (player rankings, remaining players, average chip counts, etc.). If no backplane is available, this process could likely be implemented via REST API. Simply, the parent machine could provide an endpoint like ”https://xxx.xxx.xxx.xxx:yyyy/api_name”. Child machines would pass the game-end data as parameters, receiving the MTT overall statistics data and instructions for the next game (start immediately, add participants from the waitlist, dissolve the table, etc.) as the API response.

If you chose the REST API approach in the previous section, the latter implementation method might be easier. You might think server-to-server communication could be handled via socket connections, but it seems they want to keep servers loosely coupled network-wise, so synchronous connections like sockets aren’t generally used. This is apparently to avoid the risk of all servers crashing simultaneously.

An alternative approach could involve child devices writing information to a database, with the parent device periodically monitoring (polling) the data. However, database polling is a heavy-load operation and should be avoided whenever possible. Well, the author does hold the bias that quite a few developers might choose database polling as a last resort…

After Recruitment Deadline, Game End

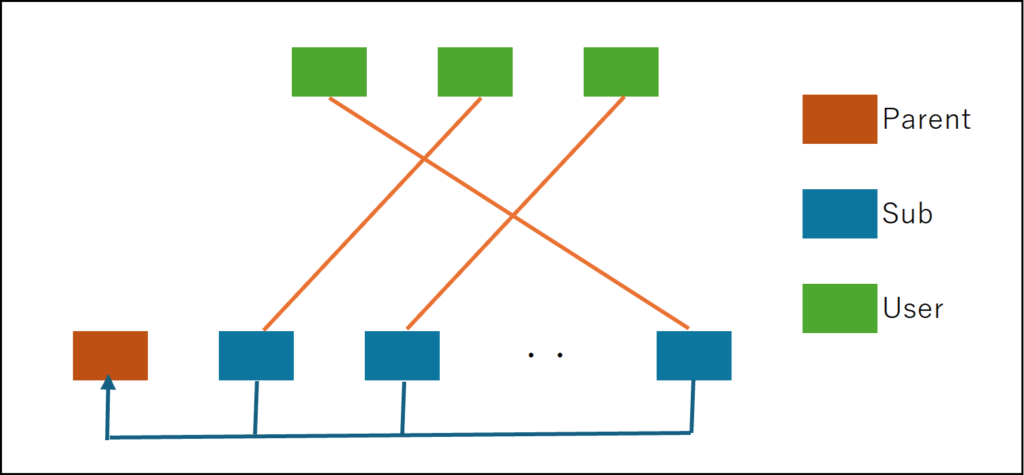

After the recruitment deadline, only the game progression processing needs to be executed. As the number of tables decreases, cross-server table reconfiguration will become necessary. This can be handled by disconnecting old child units and reconnecting new ones, thereby moving the connection between the client and the child unit. Players in a waiting state will maintain their connection to the old child unit, awaiting a relocation instruction from the parent unit.

When using auto-scaling via cloud services, server migration via reconnection is difficult. Instead, using a backplane to relay messages between users allows gameplay to continue among users connected to multiple servers. For example, when a user sends an action message to a table on a different server, the path is User -> Connected Server -> Server holding the table info. Conversely, when the server holding the table info sends a message to the user, communication follows the reverse path.

The game ends when all but the last player drop out. At game end, the child machine receives an end notification, and threads managing game progression perform termination procedures. Data requiring database storage, such as ranking data, is saved to the database by the parent machine.

Handling Failures

Up to this point, we’ve assumed all processing occurs without failure. In reality, situations like socket connections dropping or client devices crashing may occur. We won’t consider the parent device crashing here since it’s unavoidable, but let’s devise recovery strategies for these two cases.

First, if the socket connection between the client and a child machine simply disconnects, reconnecting should suffice. The parent machine holds information about which child machine the user was connected to, allowing reconnection to that child machine using the same procedure as the initial participation request. In this case,

- we need to decide:

- How to handle game progress during the disconnection period

What to do if reconnection doesn’t occur within a certain timeframe

For case 2, it’s better to set a deadline: if reconnection doesn’t occur within a certain time, the player should be treated as having left. In tournaments, players who only Check or Fold tend to survive surprisingly long, and they can be seen as annoying and stressful by other players. Therefore, it’s preferable to kick them out after a short time (around 1-3 minutes).

Regarding a situation where an entire client device crashes, the basic handling would be the same as when a socket connection is lost. However, since the game cannot proceed, players connected to the dropped client on the parent machine should be placed on a waiting list. If they reconnect, Table Rebalancing should assign them to a new table on a different client.

Will this cover all necessary processing? It looks complex, and some aspects might only reveal gaps after actual implementation and testing. Writing a perfect specification from the start seems difficult. I’ll implement it first and add notes later if I encounter any issues.

So, Which Way Should We Implement It?

For my game, I’m tentatively planning to use Google Cloud and try a distributed approach with Kubernetes. It seems more convenient to use only the resources needed when needed (since I want to experiment with using a lot of resources for short periods). The decision might come down to whether the low per-unit cost of rental servers (machines with similar specs seem to cost about half as much as cloud services) or the pay-as-you-go model with auto-scaling is more cost-effective. Technically, this requires making the server logic stateless, which I haven’t done before. But since I’m building it anyway, I figured I might as well give it a shot.

Comments